By Matt deGrood, Amelia Winger

April 29, 2024

Article link

Ever since the Houston Police Department announced it had suspended around 10% of all incident reports since 2016, citing a lack of personnel, Mayor John Whitmire has used it to assert crime is much worse than reported.

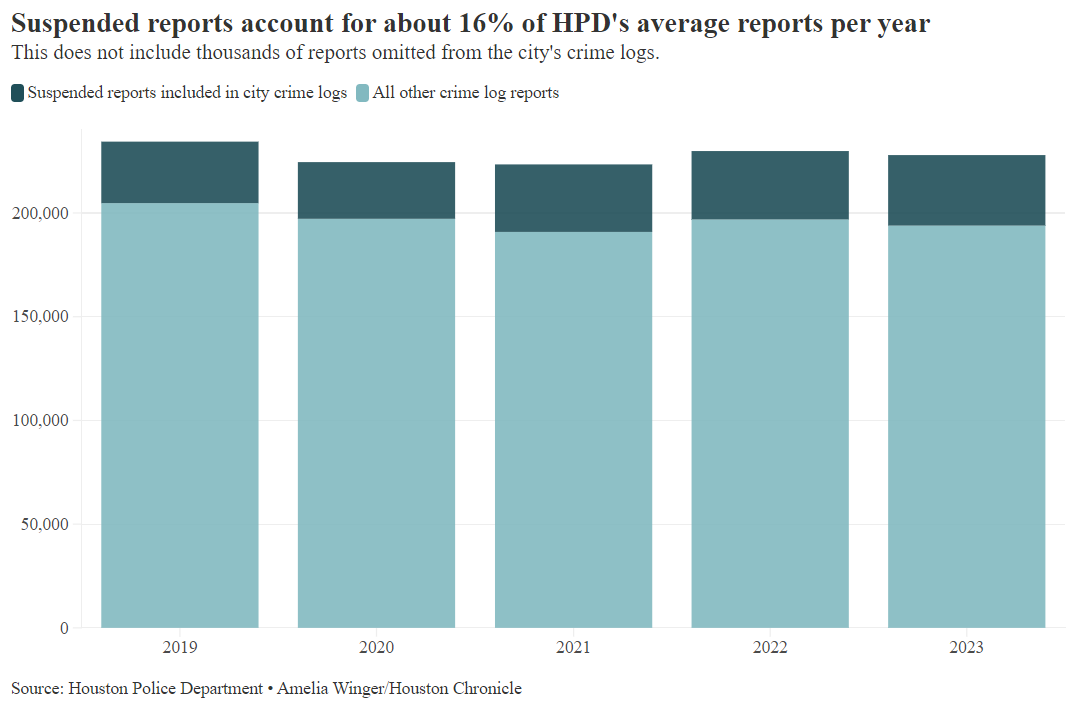

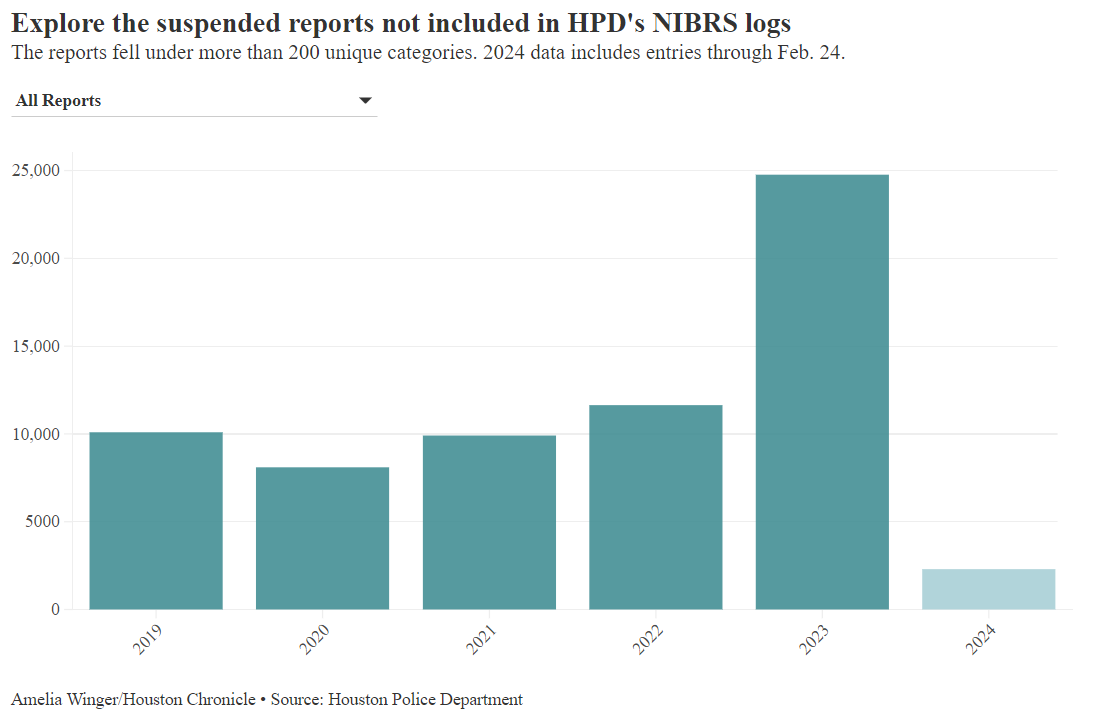

A Chronicle analysis, however, found the suspended reports’ impact on the city’s overall crime statistics will be difficult to determine. The department has received nearly 224,000 incident reports since 2019 that have ultimately been suspended due to lack of personnel, and more than 70% of those were included in the department’s crime statistics. Experts suggest the near 67,000 remaining suspended reports could’ve been omitted from the city’s crime statistics for several reasons, including clerical factors and the reports potentially not being for crimes.

Chief Troy Finner told journalists in February that he wouldn’t be talking about department clearance rates until his office gets a hold of what this discovery means.

Weeks after Finner’s initial announcement, Whitmire appointed an independent panel to investigate the suspended reports, describing the matter as a “terrible mistake” that “manipulated” the city’s crime statistics for years.

Houston police’s crime statistics come from its submissions to the National Incident Based Reporting System, a record management system used by police departments nationwide. The system tracks 62 types of crimes. Houston police began using NIBRS in 2019, and in compliance with the program’s requirements, releases logs tracking all criminal offenses in its jurisdiction.

Alongside NIBRS, the department maintains its own internal record system. This is a common practice across police departments nationwide, said Jeff Asher, a New Orleans-based criminologist and cofounder of AH Datalytics. A department’s internal system may not be a carbon copy of the NIBRS model, but they’re typically similar.

“They should rhyme even if they don’t match entirely,” Asher said. “Certain things will change, like if you have an incident in the system as an aggravated assault, but it doesn’t meet the FBI’s definition, just the state definition. So there’s various circumstances in which the exact numbers don’t match.”

For example, about half of the suspended reports omitted from Houston police’s NIBRS logs are for incidents categorized as Failures to Stop and Give Information. These are considered criminal offenses under state law, but a department spokesperson said they don’t cleanly correspond with a NIBRS-reportable category – except if a NIBRS-reportable offense was committed during the same incident.

Edward Claughton, founder and CEO of PRI Management Group, which advises police departments across the country on records management, said most police department’s divide things between case status and disposition. The statuses – open, closed, cleared by arrest, cleared by exception and unfounded – are standardized and are what is reported to the FBI. Case disposition represents the final outcome of a case and is much more customized from police department to police department. Examples of a case disposition might include warrant issued, referred to other jurisdiction, pending prosecution, suspended, inactive, victim refused to cooperate and prosecution declined, Claughton said.

Police are only supposed to include criminal offenses in their NIBRS data, Asher said, so using an internal record system can help them track incidents that may have yet to be proven criminal in nature.

“You’re acknowledging the things that you don’t know,” Asher said. “You’re still investigating, you’re serving the public. You may not have an answer. That doesn’t mean you shouldn’t try to get an answer.”

About 39% of the suspended cases omitted from the NIBRS data were for incidents dog-eared as investigations, including 1,686 homicide investigations and 788 rape investigations.

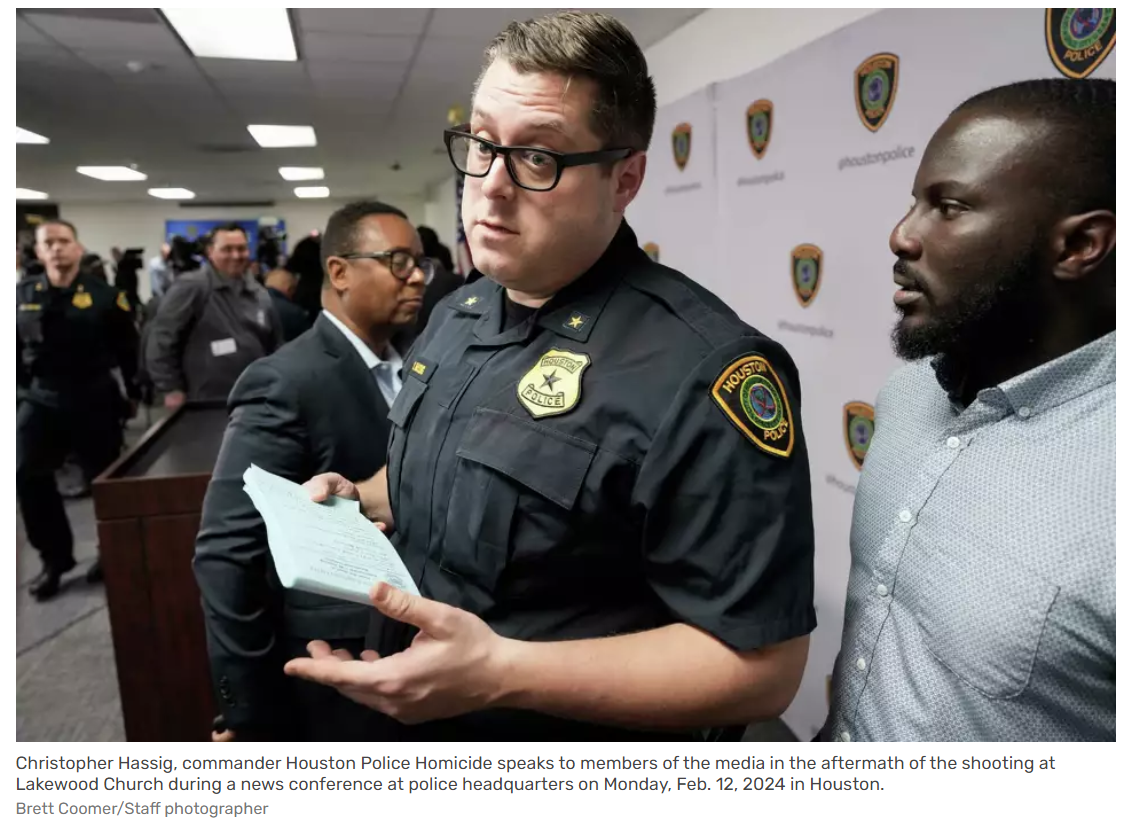

Christopher Hassig, commander of the department’s homicide division, said many of the items categorized as investigation in his division don’t wind up being a crime.

“It’s kind of funny, we kind of become the catch-all division for patrol officers,” he said. “The joke is, when in doubt, label something ‘Investigation – Homicide.’”

When something is labeled “investigation – homicide” that assigns the incident report to the homicide division and then investigators are tasked with deciding whether there’s validity there or not.

But once these cases are categorized as “investigations,” progress can languish, according to the Chronicle analysis.

The earliest case categorized as an investigation into homicide was first entered into Houston police’s record management system in November 2016, and hasn’t been touched since July 2018. For nearly 90% of the suspended homicide investigations, officers haven’t reported any new activity since at least 2022. The department did not say whether it has a process for periodically reviewing its backlog of suspended incident reports to determine if they have the bandwidth to resume investigating them.

In a social media post shared earlier this month, Houston police officials said some of the suspended reports were filed for civil – not criminal – matters, like insurance claims, suspicious circumstances and other reasons solely related to documentation purposes. It’s why officials have insisted on using the term “incident reports” when referring to the suspended items, despite initially calling them “cases.”

Police Chief Troy Finner first announced the department had suspended cases in late February, launching an internal investigation into the matter that is expected to conclude as early as the end of this month. He said he instructed officers to stop using the code in 2021, though data shows the number of suspended reports continued to balloon after he gave the order.

“That code was put into effect in 2016. It will not be used again in my administration,” Finner said. “It was unacceptable then. It’s unacceptable now.”

0 ITEMS

0 ITEMS